Face Seal System VS Rainscreen System

The construction industry has adopted two major strategies on the cladding to protect building structures from water damage. They are the “Face Seal” and “Rain Screen” system, and today we are going to briefly go over them so you know what to expect to see in the wall.

How does water get into a building?

The 3 mandatory requirements for water to enter a building are:

- Water needs to be present.

- A hole for water to enter.

- A driving force to push the water in.

If you remove any one of these requirements, then water cannot enter. Naturally, the construction industry starts finding out ways to eliminate these requirements. The most effective way is to avoid water from contacting the building surface, but it is practically impossible to provide overhangs everywhere in a building. Since we cannot control the pressure difference to eliminate the driving force, people naturally gravitate towards the second option: to eliminate holes water can enter.

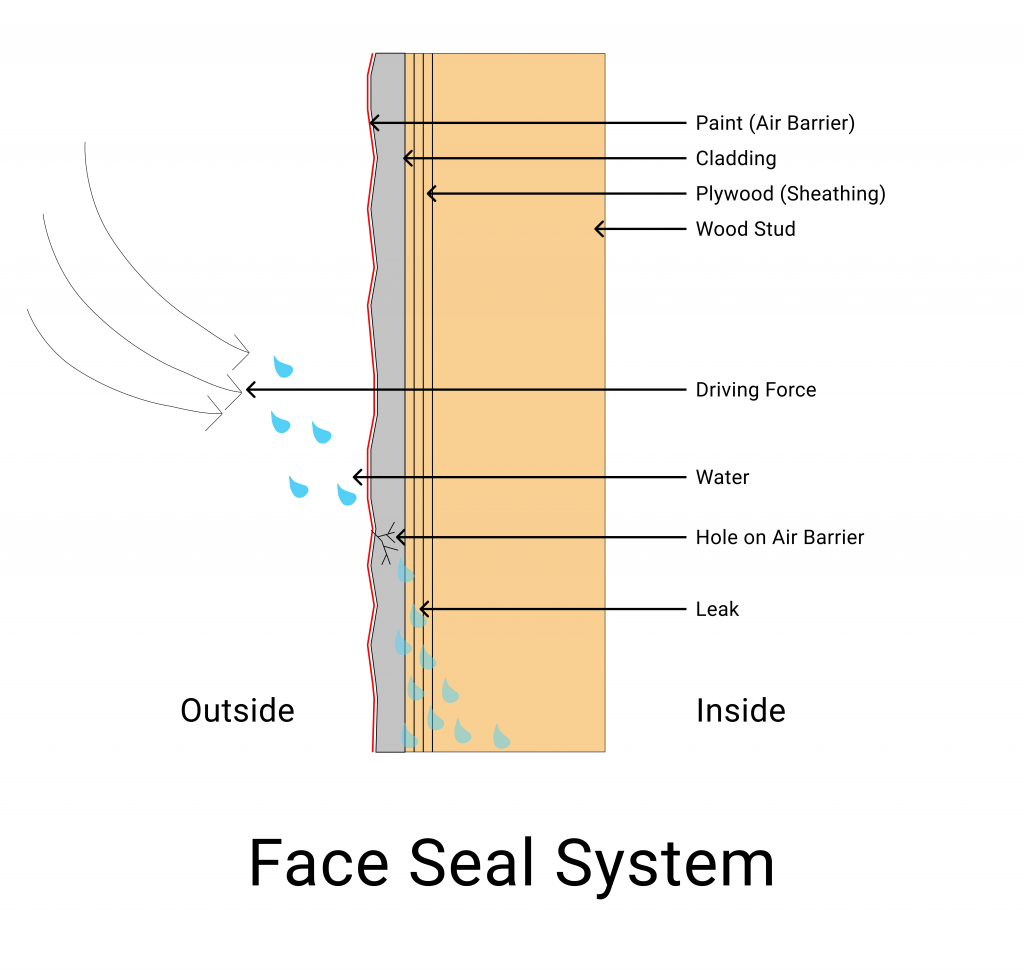

Face Seal System

The concept for the face seal system is simple, to eliminate any holes so no water can enter. It would have worked with flawless contractor workmanship in a perfect world without thermal expansion and condensation. What I mean is, although the concept is simple, the high maintenance requirement and the low margin of error are not proportional. In the 1980s when the face seal system was popular, not many contractors were doing things right. As the name suggests, any water that gets into the face seal system, has no way to leave the system either. This directly resulted in Vancouver’s leaky condo crisis in the year 1998.

What is Air Barrier?

Before we start talking about the other system, we need to first clarify what is an air barrier. The air barrier is a conceptual term to denote the element with the most air-tightness in a wall. It doesn’t have a hard rule on materials or applications, but simply a layer to prevent air movement. Naturally, the two sides of the air barrier have the highest air pressure difference between inside and outside. In the scenario of a face sealed system, the air barrier is the exterior paint applied to the cladding. They are exposed to the weather like snow and heavy rain. Direct sunlight may cause the paint to become brittle. With thermal expansion and contraction, it would be a miracle if the paint does not crack.

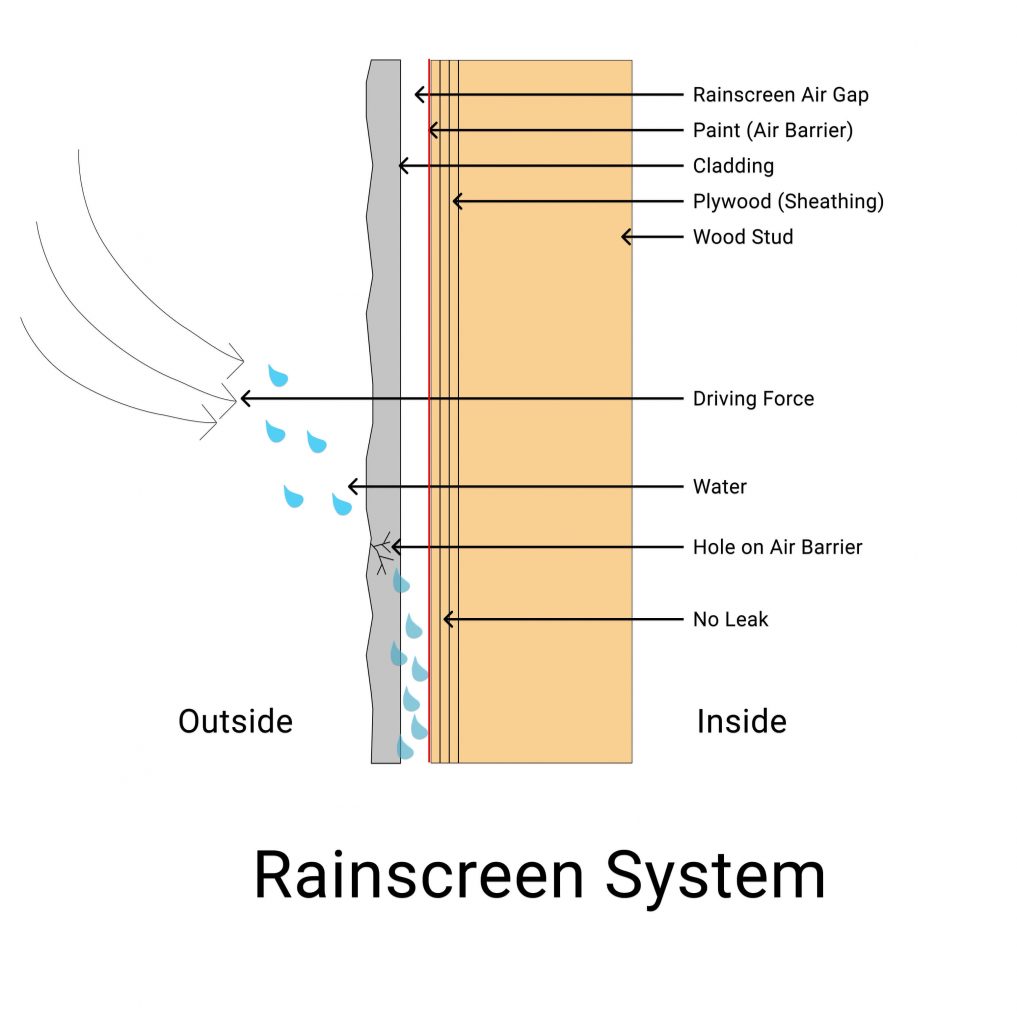

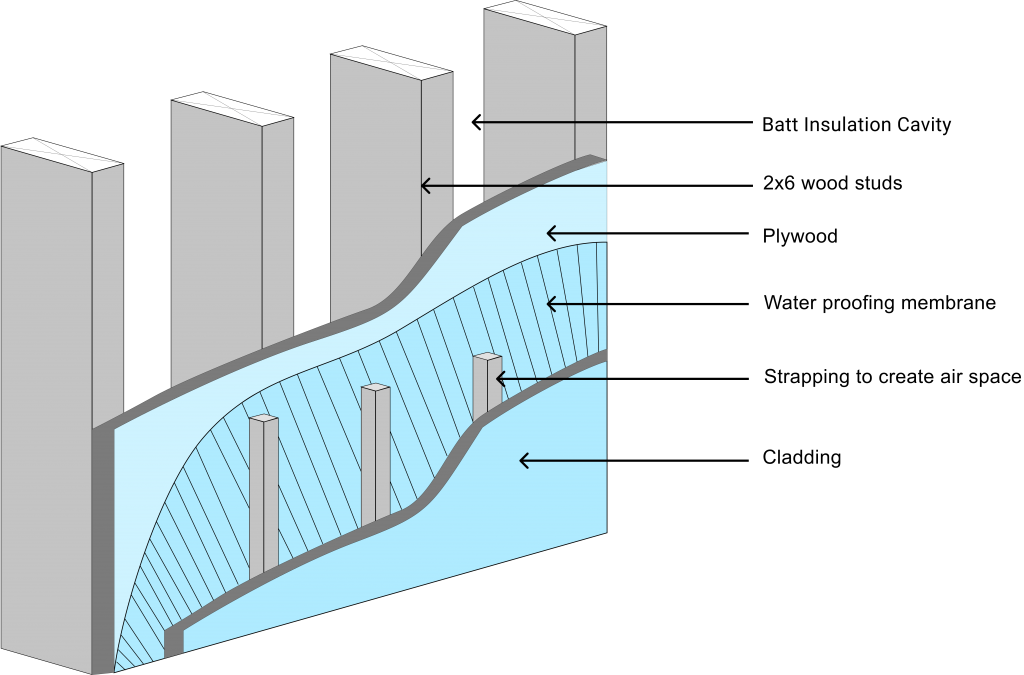

Rainscreen System

After many cases of building envelope failure with face seal system, the 1996 version of the Vancouver Building Bylaw has made rain-screen system a prescriptive option for exterior wall construction (Required after 2007). This type of construction method is based on a Norway study in the early 1960s. It shifts the air barrier behind cladding while creating a ventilation/drainage layer in between. This method assumed our exterior cladding cannot completely divert 100% of the water from outside. With that assumption, the cladding’s job is only to protect the air barrier from the majority of the water. Any water that gets through the cladding layer will have a chance to drain away or dry out through the ventilation layer. In this scenario, even when the air barrier remains the area with the highest driving force, water and holes are unlikely to be present at the same time.

Why do we still talk about the Face Seal System?

You might be wondering why we are still talking about Face Seal System when the Rainscreen is already a prescribed requirement in the building code. Truth is, even after decades of proven failure for the face seal system, they are still around in the older buildings. These buildings are typically built before the bylaw changes. We are bringing up this topic so the potential buyers can be aware. Also, if you are doing renovation for a building built between 1980 and 2007, then chances are you are dealing with a building using the face seal system. In that case, no one can guarantee what you will see after you open up the wall.